Courage and Cowardice

June 04, 2013

What is courage? Trying to pin down a clear definition can be difficult. For many of us, it may be easier to remember times when we've lacked courage - responding to difficult situations with fear or indifference. While it may not always be comfortable, such honest self-reflection may help us better understand how fear operates in our daily lives. Ultimately, we may learn how to channel it in a positive direction. From this perspective, learning about fear and cowardice can be a self-empowering step toward living more courageously. As civil rights leader Rev. James Lawson has said, courage is "discovering how to face your fears and moving through them as a whole person."

As part of our ongoing exploration of the virtue of courage, we would like to take a look at the relationship between courage and fear through the following article titled "Courage and Cowardice" by author Anthony McGowan. The article was originally published in the July 2012 issue of SGI Quarterly.

"Courage and Cowardice"

by Anthony McGowan

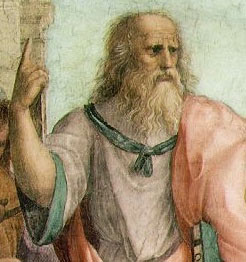

Plato's early dialogue on courage, Laches, points up the difficulty in pinning down what we mean by courage. All the definitions we reach for seem either to be excessively restrictive, or unnecessarily permissive, gathering in too few or too many of those moments of resolve or recklessness that we recognize as instances of bravery.

Laches (extract), a Socratic dialogue written by Plato presenting competing definitions of courage

Casting around, one finds two competing paradigms of courage. The old-school definition makes courage synonymous with fearlessness. The hero, as generally conceived, seems to have this quality--lightness in the face of danger, a certain swagger. Our hero, from Galahad to Captain Scott and on to Luke Skywalker, might be permitted to smile regretfully at the lost future as he confronts his (usually his, of course) nemesis, but never will his soul quake.

Coming up on the rails is a contrary view--that true courage, in fact, precisely involves the overcoming of fear. The soul must quake before resolution stiffens it. This view may be less heroic, but it adds a psychological realism, for who has not achieved at least the first part of this definition of courage?

Image: Plato from The School of Athens (detail). Fresco, Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican.

Credit: Raffaello Santi (Attribution via Wikimedia Commons)

The soul must quake before resolution stiffens it.

But the truth is that these remain words, and they struggle to gain purchase on the world of lived experience. So I've tried to dig down in my memory to find examples of courage to add flesh to the wraithlike concept.

The first real job I ever had was working in a UK tax office. I was straight out of university and, frankly, didn't have a clue. I was lost and hopeless and unhappy. My line manager was a person quite out of my experience. Let's call her Norma. Clearly once a great beauty, now, approaching retirement, Norma was, to me at least, genuinely terrifying. She could see through me, and left me stuttering, blushing, lamely defending myself for my latest error or miscalculation.

But I got by. I survived by surrendering. By paying court. By offering her the elaborate compliments she demanded. She outgunned me, and so I struck my colors.

But then another person joined our team: Sarah, a dumpy, happy, not very bright former primary school teacher, who didn't know how to use apostrophes and whose best friend was the budgie she used to let fly freely around her tiny flat. I was rather fond of her, and I tried to show her the ropes. My boss, however, hated Sarah. Something about her plainness, and the lack of interest that she showed in her dress and hair, enraged Norma. And so a campaign of persecution began. Cutting remarks came her way, along with the nastiest and most tedious office jobs. Sarah was frequently driven to tears. After a couple of months, she left.

And me, what had I done to protect her? Nothing, except offer quiet condolence and eye-rolling sympathy at Norma's latest sally. I never confronted Norma with the unfairness of her conduct, never publicly stood up for Sarah. Why not? Because I was afraid. Because Norma had power and presence, and I was a coward, and I feared the embarrassment and awkwardness my intervention would cause. And because of my cowardice, a person's life was made worse.

Brave, True and Just

For my example of positive courage in action, I'm going to have to travel yet further back in time. Back to a period when almost every day held a challenge, a conflict, a moral dilemma: the raw material from which cowardice and courage are formed. My school was on the outskirts of Leeds, where the city, in the face of bogs and fens and scrubby moorland, loses its will to go on. Leeds back then was poor. And hard, and this toughness found its apogee in my school. It was a place where bullying and violence saturated the air like the Leeds rain.

Dean Taylor was in my class. He was one of the kids in a carefully pressed blazer, his hair combed into a side parting, his tie neatly knotted, who draws bullies the way grime loves a fingernail. His chief tormentor was a kid called Merton. Merton wasn't the worst of the hard cases, but for some reason he had it in for Dean. Random punches, sly, back-of-the-head slaps. The routine trippings and dead-legs that make school playtime a little hell to be endured.

Dean, like the rest of us, put up with this sort of thing. We put up with it partly through physical fear--the thought that the punches would get worse if we snitched--but much more through the huge social pressure, the law which says, Thou Shalt Not Tell.

And there were more subtle pressures. Drawing attention to the fact of being bullied meant adding to the humiliation. It was exposing your weakness to further ridicule, to mockery and to pity.

What had happened, I think, is that our world--the hard kids and the quiet, even Merton and his crew--suddenly saw that what Paul was doing was brave, and true, and just. And in the soul of every human, there is something that makes us bow our heads before such things.

But Dean had something the rest of us lacked. He had an older brother, called Paul. Paul was just a year older, and so similar to Dean in his scrawny neatness that they could pass for twins. One break time, Paul saw Dean take a punch from Merton. He then calmly took Merton by the collar and dragged him across the yard toward the school, and the headmaster's office. Merton was by far the larger and stronger of the two, and he rained down punches and kicks on Paul. We heard them land with either the crunch of knuckle on bone, or the softer, almost wet sound of knuckle on cheek.

Merton's mates joined in, turning the procession into a gauntlet. They jeered, they kicked, they tried to prize Merton away. But Paul still held on, still marched toward the office. He was bleeding by now, and his neat hair was tousled, his blazer torn. But on he went.

And then something happened. Merton stopped fighting. His arms no longer flailed down on Paul's head. The other hard kids stopped screaming, and launched no more than the occasional, desultory foray. And the whole playground was somehow transformed. The silence of the oppressed minority changed its texture. And then suddenly it was not silence anymore, but a kind of exultant murmuring. And finally a joyous cheering.

What had happened, I think, is that our world--the hard kids and the quiet, even Merton and his crew--suddenly saw that what Paul was doing was brave, and true, and just. And in the soul of every human, there is something that makes us bow our heads before such things.

So what was it that made this act from Paul so brave, so right, so courageous? Well, there was the physical danger involved. There was the huge social pressure to overcome. And there was the simple justice of the act.

And is there a lesson to be drawn from all this? Well, there is one, I think. I am haunted by those little acts of cowardice--not helping Sarah, not resisting the petty tyrants infesting the power structures of modern life. I wish that I had made my stands.

And I imagine that, in contrast, Paul and Dean will always remember that moment of bravery in the playground, when courage and justice made them mighty.

Anthony McGowan is an award-winning author of books for adults, teenagers and younger children. He has written two highly acclaimed literary thrillers, Stag Hunt and Mortal Coil. Filming began in the UK in March 2012 on the movie based on his book for young adults The Knife That Killed Me.

Comments:

There are no comments for this entry. Be the first to leave your own!